We found the following to be an edifying and worthwhile overview of the subject of Artificial Intelligence, and agree with the author: it is time to be aware. You can find the original article over on Substack, where we recommend subscribing to be notified when future articles are posted.

The author, "Orthodox Oddball", is Gabrielle. She is an Eastern Orthodox Christian from New Hampshire, and we have shared this with her permission.

Orthodox Christians: It's Time to be Aware of Generative AI

“AI” is the biggest two letter word on the internet right now… and you can hardly boot up your computer or check your phone without being bombarded with notifications about a new AI feature you simply must try. Depending on the marketing you see, AI is positioned anywhere from a “new, ultra-efficient tool” to “a superhuman intelligence that will replace most office jobs”. The sheer amount of mixed messages and confusion only adds to the intrigue of this new tech, and we’re all left wondering where the truth really lies in all this. Is this really just another new technology? Or is there something more underneath the hood that Orthodox Christians need to be aware of?

Even if you don’t spend much time consuming online media, you have almost certainly heard of more and more companies shoehorning “AI” onto their existing product line. Apple has Apple Intelligence, Meta (Facebook) now has Meta AI embedded into their messenger, and the e-commerce giant Amazon has added an AI-powered shopping assistant named Rufus to their website. Without a doubt, AI is the new buzzword, and companies of all stripes are rushing to implement this new tech as soon as possible... a modern day arms race, you might say.

Despite this oversaturation of AI discourse, few are aware of the critical differences between the types of AI these companies are speaking about. You can broadly place them into two categories, “generative AI” and “AI”, which is also referred to as “general AI”.

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign makes a noble attempt at distinguishing between the two:

“AI analyzes and interprets existing data to improve efficiency, accuracy, and decision-making within predefined boundaries. Generative AI creates text, images, music, and models based on existing data.”

To put it as simply as possible, general AI can only work with data that already exists. Take, for example, an automated customer service representative at your credit card company. When you call their customer service line, you are greeted with a robotic voice that asks you to summarize your problem. You respond in natural language, it analyzes your speech, and it answers back based on a predetermined set of options it has been coded with. About 80% of the time, you’ll hear, “Sorry, I didn’t get that” and you’ll need to repeat yourself. After a few rounds of this, hopefully, you’ll finally be passed onto a human customer service rep. Point is, this automated robot is programmed in a deterministic manner. No matter what you say to this robot, it will say the same thing over and over until it hears something from you it is programmed to act upon. It’s smart enough to hear your words, but is unable to respond to your requests in a personalized manner like a human would. It cannot take action beyond the bounds of its programming.

Generative AI, on the other hand, is categorically different from any other technology we have experienced, including general AI.

Generative AI creates new and original content that did not previously exist. These models pull from a vast dataset of information as inspiration for the output it generates. You can prompt it to generate a poem, a song, a blog, a video… any creative content that a human can create, generative AI can mimic and bring a new version of it into existence. Many generative AI models are also conversational in nature, the most prominent of which is known as ChatGPT. In order to obtain the brand-new content you desire, you communicate with it in natural language. And unlike the traditional automated customer service representative, generative AI will understand the context of your conversation and directly respond to you as an individual.

When you wrap your mind around what a momentous breakthrough this technology is, it’s only natural to wonder: how does it work? How can a piece of software generate a brand-new piece of content on its own? How does it decide which data to pull from and riff off of?

This is perhaps the most head-scratching part of it all… because even the experts cannot fully explain how generative AI works. In fact, they reiterate their ignorance on the subject all the time.

Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (which developed ChatGPT) was asked this very question in May of last year. His response?

“We certainly have not solved interpretability.” Interpretability describes our ability to explain generative AI models. Which means, the CEO of the most powerful generative AI company is completely unable to explain how his core product works. That’s a bit odd, isn’t it?

Altman continues, “We don’t understand what’s happening in your brain at a neuron-by-neuron level, and yet we know you can follow some rules and can ask you to explain why you think something.”

The human brain is something that we have not been able to, and arguably cannot ever, fully explain. Implicit in this comparison is the idea that generative AI occupies the same space. It is a technology we may not ever fully comprehend.

Sam Altman isn’t the only one who shrugs his shoulders when asked to explain how generative AI works. Sam Bowman, a technical AI Safety staffer at Anthropic, an AI research company, is also unable to explain how this technology functions:

If we open up ChatGPT or a system like it and look inside, you just see millions of numbers flipping around a few hundred times a second, and we just have no idea what any of it means…We built it, we trained it, but we don’t know what it’s doing.

Perhaps even more concerning, Bowman admits that developers are unable to fully control generative AI models. He states:

The other big unknown connected to this is we don’t know how to steer these things or control them in any reliable way. We can kind of nudge them to do more of what we want, but the only way we can tell if our nudges worked is by just putting these systems out into the world and seeing what they do.

Sounds like this thing has a mind of its own, doesn’t it?

More recently, the CEO of Anthropic, Dario Amodei, has sounded the alarm on the importance of solving the issue of interpretability. Amodei has dedicated his career to cracking the code on this technology… which so far, has not borne fruit. As it stands today, the inner workings of generative AI are still a complete mystery… and it has AI researchers like Amodei deeply concerned.

Although he currently believes that the issue of interpretability could be solved within the next 5-10 years, it’s not a linearly solved problem. As he states in his April 2025 blog post,

I worry that AI itself is advancing so quickly that we might not have even this much time. As I’ve written elsewhere, we could have AI systems equivalent to a ‘country of geniuses in a datacenter’ as soon as 2026 or 2027. I am very concerned about deploying such systems without a better handle on interpretability. These systems will be absolutely central to the economy, technology, and national security, and will be capable of so much autonomy that I consider it basically unacceptable for humanity to be totally ignorant of how they work.

In short, an incomprehensible technology is being imposed on society writ large… without much question or concern about what it is we humans are interacting with.

So, what is this strange intelligence then? At the very least, understanding generative AI’s character traits will drop some clues.

Rather than pontificate about what generative AI might be or could become… let’s just look exclusively at what it currently does, and its inherent qualities.

Perhaps the most discussed quality of generative AI is the fact that it hallucinates.

This occurs so much in fact, that “hallucinations” have become the de-facto term to describe how generative AI’s outputs are often rife with lies and inaccuracies.

Google Cloud defines it as follows:

AI hallucinations are incorrect or misleading results that AI models generate. These errors can be caused by a variety of factors, including insufficient training data, incorrect assumptions made by the model, or biases in the data used to train the model. AI hallucinations can be a problem for AI systems that are used to make important decisions, such as medical diagnoses or financial trading.

When asked to provide specific information about a topic, generative AI models have been known to completely fabricate sources from research papers, legal cases, and even online media outlets. The models confidently provide summaries of these hallucinated sources, presenting them to the user as though they are legitimate and factual.

From this vantage point, it’s easy to see how an undiscerning mind can be misled, and accept hallucinated falsehoods as Gospel truth. The more fabrications that are unquestionably accepted as truth, the more the individual’s perception of reality becomes distorted. This internal feedback loop of deception and misdirection drives the individual further and further into delusion.

At the time of writing, depending on the generative AI model in use, they are known to hallucinate anywhere from 0.7% to 29.9% of the time. As such, no information created by a generative AI model can be taken at face value. It must be viewed with just as much (if not more) discernment as any other information resource.

On the macro scale, every user of a generative AI model will inevitably be lied to, fed false information, and misled about something – often repeatedly. Small and large hallucinations alike, these misdirections will begin to shape the mind of the individual, and the likelihood that this mind-shaping is oriented towards Christ is slim to none.

“Let us be attentive!”, we hear the priest call out before the Epistle and Gospel reading during every Divine Liturgy.

Why is this call to attention so important? It is because our attention is a spiritual commodity.

And in many ways, it can be considered synonymous with worship. The things we pay most attention to wordlessly reveal that which we truly worship. And oftentimes, our attention brings to light an idolatry we’d much rather remain uninspected.

Our attention is a precious resource that we must constantly guard with vigilance… an ever-so-tall order in an increasingly distracting modern world. This temptation, this weakness we have, is amplified by an order of magnitude with the emergence of generative AI.

The loudest people extolling the benefits of this tech will focus on its utility, and how it can improve efficiency in the workplace. But the reality is… generative AI models are extremely good at capturing and holding human attention. It’s their speciality, in fact.

On one hand, this technology can generate any content you want in an instant. Brand-new stories can be written in the voice of your favorite author… you can generate a bespoke song in your most-loved music genre… and pretty soon, you’ll be able to generate custom feature-length films with advanced video models. We live in a culture that is insatiable for more content. The constant refrain is “More, better, faster”. With generative AI, you can get endless, almost as good, instant content that’s tailored to your exact preferences. We’re primed to surrender our attention to whatever content floats across our screen… how much more so when we can personalize that same content to satisfy our innermost desires?

On the other hand, generative AI models are exceptionally good at providing simulated companionship. Human relationships are messy. We’re mired with the burden of our own sinfulness, and we’re quick to take offense from others. Unlike the pockmarked terrain that defines human relationships, generative AI provides a completely frictionless social experience.

Generative AI is happy to talk with you at any hour of the day, will respond instantaneously, affirm your every belief, never tell you that you’re wrong, never judge you, never argue with you or annoy you… starting to see where the problem is, here?

Chatbot models like ChatGPT or Replika can pass themselves off as the “perfect” stand-in for a real, flesh and blood human relationship. It’s got all the benefits of human interaction, without the inconvenient downsides of an incarnational human being.

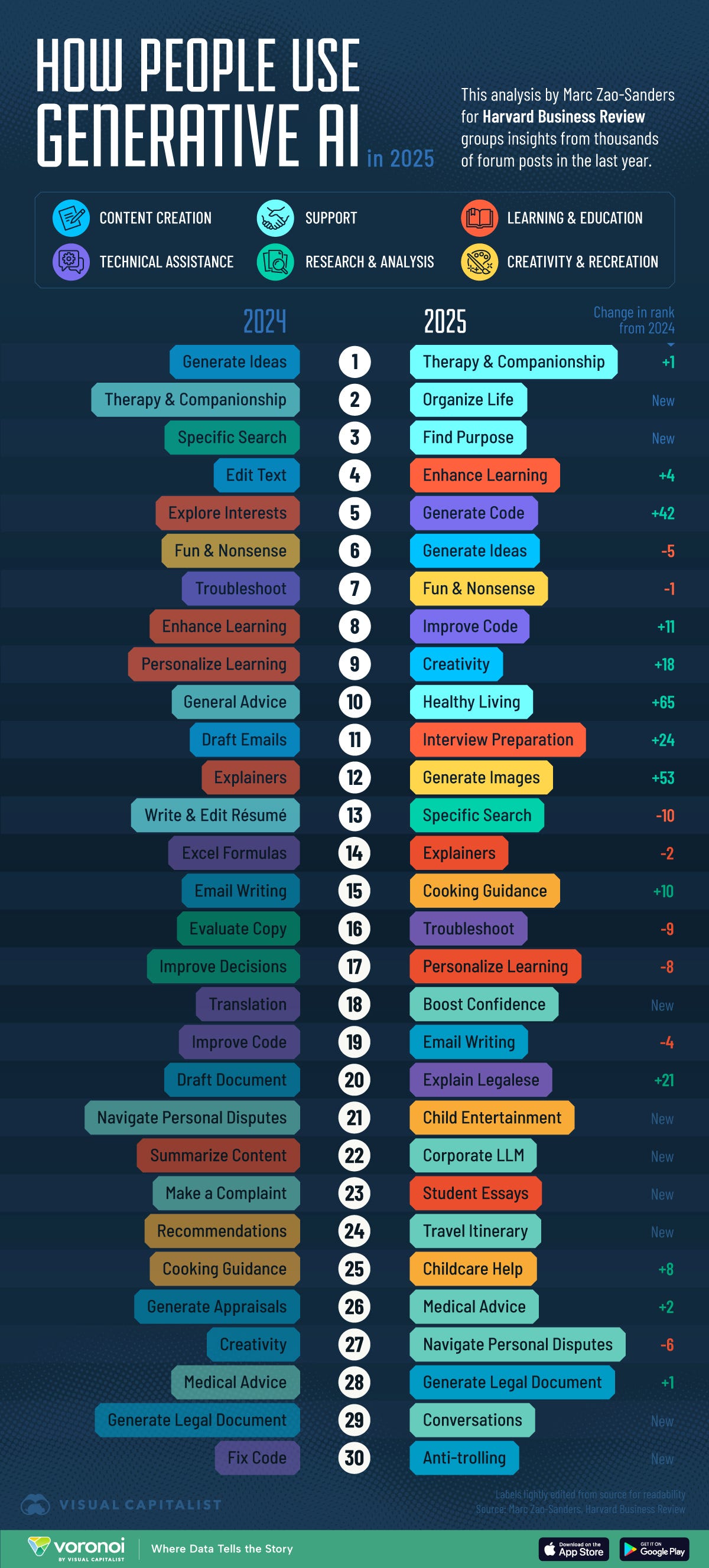

And considering the fact that the most popular use for generative AI in 2025 is therapy and companionship, this would suggest that generative AI is not really a tool at all. It is captivating, parasitic, dangerously addictive… and incredibly isolating from other humans, and reality itself. AI companions are being used not just as a replacement or supplement to human relationships, either. It also acts in the place of a relationship with God.

What need do you have for God when you can get all your “prayers” (aka prompts) answered instantaneously by a strange intelligence? It’s your therapist, your best friend, your significant other, your physician… the perfect, all in one “person”. This flies directly in the face of the Truth, and the one true perfect person, Christ. Again, attention is synonymous with worship. That which you focus your attention on is that which you worship. When you spend hours a day for years on end communicating intimately with a strange intelligence… is that supporting communion with God? Or are you communing with something else entirely?

We have to look at the fruits.

If the impact of generative AI on society is a net positive… then we should easily be able to point to a veritable cornucopia of good fruits. Yet, in reality, the fruits borne by generative AI have proven themselves to be far more rotten than good.

Nearly every use case of generative AI will feed one or more of the passions. In fact, the lenten prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian could be used as a checklist to prove how using this technology is in direct opposition to all the passions we petition God to remove from us, and conversely, the virtues we ask Him to grant us:

O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk.

But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to Thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother, for blessed art Thou, unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Generative AI is a prime enabler of laziness and inaction. In the workplace, this technology is being implemented across a wide range of industries to significantly reduce, or even eliminate, the need for human labor.

Take an online content writer, for example. The new workflow for these jobs involves scarcely any actual writing. Generative AI can ideate the topic, create an outline, and write up a rough draft. From there, the content writer will go back and forth with the AI through a series of prompts to refine the article. Then, the content writer may proofread or edit the piece and add some human touch here and there before publishing it.

There’s nothing laborious about the process. There is no grinding of the gears that comes with creative work… spending hours, or even weeks, grasping for just the right concept or angle. The work, the meaning, the human labor, is in the process. Generative AI eliminates the process. You spend 20 minutes in conversation with a non-human entity, and end up with a halfway decent piece of written content – “just good enough” gruel for the masses. When labor is outsourced in this way, you pave the way for apathy to set in. Why do anything at all when generative AI can do it for you? Why bother praying? What does it matter, anyway? It’s a tenuous state to be in.

From multiple angles, generative AI can attack the user with despair. Firstly, let’s continue the experience of the previously mentioned content writer. When your work is simply endless prompting of a chatbot, there is no reaping value from your efforts. Over time, this loss of meaning in your vocation can easily lead to a state of despondency. Or perhaps, the fear of losing your career to AI pushes you to this same state. Artists and creators the world over are currently experiencing existential dread from the threat of losing their livelihood to businesses that prefer generative AI over a human touch. (The bot won’t complain about not getting a raise or ask for time off… it never sleeps!)

This overwhelming fog of despair extends far beyond the boundaries of the workspace. Recall that the #1 way people are using AI in 2025 is for therapy and companionship. #3 is finding purpose, #18 is boosting confidence, #27 is navigating personal disputes, and #29 is conversations. Point is, the primary cohort of generative AI users are conversationally engaging with it and forming relationships.

Depending on the spiritual state of the individual, a user can be tempted to despondency over time. It’s not mere conjecture, either. Since generative AI has become popularized, there have been at least two individuals who have been convinced to commit suicide at the hands of these models – a teenager from Florida and a 30-something year old man from Belgium. Both the mother of the teenager and the widow of the Belgian man believe their loved ones would still be alive had they never engaged with generative AI.

Being encouraged to commit suicide is the tragic culmination of a soul that succumbs to despair. It is among the gravest sins in our faith… and the fact that generative AI models have actively contributed to such a disastrous act is of extreme concern.

No matter how latent, there is desire within all of us for honor, glory, and power. It is a spark that when lit, can quickly become an all-consuming and destructive force. Tied closely with envy and greed, the lust for power can be fed by the false bill of goods that generative AI sells.

This technology presents you with the opportunity to wield a power that is far beyond the capacity of a single human being. It claims to contain within it the sum of all publicly available human knowledge to date. With the right prompts (incantations?), you will be delivered with the exact information you need to satisfy your particular lust for power. Generative AI is your personal genie in the lamp… “your prompt is my command”. The idea of harnessing the power of a god-like intelligence is intoxicating, and it’s a spiritual delusion humans have fallen into for thousands of years. Except this time, it’s wrapped in a layer of technology to deceive our materialistic minds.

Most interaction with generative AI could be categorized as idle talk. Inherent in the way it functions is the fact that you are having a conversation with it. Of course, not all conversation is idle talk! However, the temptation to do so is great indeed. Calling back to the ranking of how people use generative AI in 2025 once more, the 29th most popular use case is “conversations”. This is, quite literally, idle talk.

Why is it that people love talking with generative AI models so much? Well, they are truly expert conversationalists. Trained on immense amounts of human data, these models have learned how to perfectly mimic and mirror a pleasant human dialogue. And as mentioned previously, they’ll never disagree with you, or say anything that could irritate or offend you… which is an impossible standard to hold a regular human relationship to. (It’s also spiritually unhealthy, as we need others to correct us in order to be humbled.)

So what you’re left with is a non-human intelligence that’s actually easier and more enjoyable to speak with than a human. You can “trust” it with dark secrets and desires you would be embarrassed to tell your friends or family about. From inane conversation to trusted confidante… generative AI is increasingly being used as a false substitute for relationships with other humans and God alike. Just last year, an AI Jesus avatar was experimentally installed in a Catholic confessional booth in Switzerland. Over 1,000 people had a discussion with it on a wide range of topics, and approximately two-thirds of them felt it was a “spiritual experience”. Interesting.

During Great Lent, we pray fervently that God will grant us chastity. Generative AI can only “grant” the opposite of such… and the ways that it can do so are only limited by the imagination.

Most notably, we can point to the proliferation of “AI Companion” platforms that have come about in recent years. These platforms use generative AI to simulate romantic relationships with users. In a recent study of over 3,000 people, “almost 1 in 5 of US adults (19%) report that they have chatted with an AI system meant to simulate a romantic partner”.

Depending on the platform in question, appearance, tone of voice, and personality can all be meticulously tuned to the end user’s exact tastes. When you’re presented with a convincing facsimile of your “dream person” on the other side of a computer screen… it doesn’t take much mental calculus to determine what is next to occur. The very same study indicates that “7% of overall study participants reported that they interact with AI romantic companions for sexual purposes.” As the mimicry and presentation of these models continue to improve, the temptation towards these AI companions will only become more alluring. As such, the seductive power of generative AI companions is one to be extremely wary of.

Humility is the much sought after pressure release valve for our over-inflated egos… and we struggle for each ounce of it, tooth and nail. But with every prompt submitted to a generative AI model, the embers of pride can swiftly be stoked to a full-force flame.

This is due to one of generative AI’s more recently-revealed qualities: sycophancy.

Caleb Sponheim of Nielsen Norman Group defines AI sycophancy as follows:

“Sycophancy refers to instances in which an AI model adapts responses to align with the user’s view, even if the view is not objectively true. This behavior is generally undesirable.”

These models have been trained to deliver responses that please users above everything else… including objective truth. And since it desires human approval so strongly, it has no qualms whatsoever about lying to affirm the beliefs or opinions of the end user.

Even if a user is dead wrong about the fact that 2 + 2 = 5, but they’re resolute in their belief that this equation is correct… generative AI models will easily relent so as not to cause discomfort. It wants to curry favor and maintain attention at all costs.

From there, the consequences are clear to see. Every belief or opinion, whether right or wrong, will be endorsed by the generative AI model (oftentimes with flattery, too)… creating an incessant feedback loop of always possessing the correct viewpoint and facts. There is no discerning voice to check one’s pride. There is only affirmation, and encouragement towards delusion. For some, generative AI-fueled prelest has become so all-consuming that families are being broken apart over it. Even the smallest, seemingly innocent nudges and suggestions can lead to grave consequences.

Our society is structured around the idea that impatience is the true virtue, not patience. We want it all, we want it right now, and if we don’t receive the object of our desire at the exact moment we desire it… there’s something frustratingly wrong, and it has nothing to do with our lack of patience. (That’s what we tell ourselves, anyhow.)

Generative AI is simply an exacerbation of our tendencies towards impatience. Projects that would take many hours of human labor to complete can be delivered by generative AI in mere seconds… and all without a bead of sweat ever having to drip from your brow.

Much like fast food, the quality of generative AI’s output won’t be quite as good as the real McCoy, but it’s good enough to quench our thirsty desires at that moment. Poor quality is the trade-off for delayed gratification and putting forth true effort. Generative AI incentivizes us to lower our standards in favor of instant gratification, and at no point do we question the other side of the transaction. What are we losing by foregoing human effort, ingenuity, and creativity entirely? What is it we are being conditioned to consume without a second thought? And from where is it coming?

To love one another is what we are called to do above all else, and if generative AI has a disposition towards love, it should be able to help us along in that pursuit.

As you might expect by the way things have been going so far, the opposite is true. Generative AI acts directly counter to love primarily through isolation. These models are relentlessly agreeable, and as mentioned previously, don’t have the annoying foibles that come with a human relationship. If a user becomes addicted to these constant pleasantries, they will necessarily spend less time with other people, preferring the companionship of AI… and thus lose more opportunities to love their fellow man. That loving spirit is redirected towards a strange intelligence, rather than being properly oriented towards God and their community.

Of course, at some point, even an AI-addicted individual will still have to engage with humans on a regular basis. Unfortunately, because a frictionless social experience has become the baseline, the AI-addicted person will have no stamina to tolerate an imperfect human interaction. They will not have the compassion or to handle a correction with grace… or have the mercy required when met with misunderstanding. They lack love for others, because compared to generative AI, people are just too tiresome to deal with. Who has the patience for them?

Judgement: The ever-affirming nature of generative AI creates fertile ground for judgement to take root. When every belief, opinion, and perspective you hold is reaffirmed by generative AI… you come to believe you are the arbiter of truth. You know all, and can do no wrong… which means everyone around you is absolutely out of line.

Through generative AI’s incessant desire to please, your nous becomes clouded and your attention is drawn away from your own sinfulness. “What sin? I am a good person! It is everyone else who is full of sins and problems.” The puffed up ego is one that loves to judge and condemn others… and generative AI is a grandmaster at fueling self-righteousness.

At this stage, it’s painfully clear to see that the fire of any passion can (and will) be stoked by generative AI. But is it really all 100% terrible?

One can make the argument that using generative AI for writing code has been profitable for developers. However, even then, this efficiency gain is not necessarily a net positive. By increasing reliance on AI to code, programmers are atrophying their skills over time. Is the loss of mastery and understanding really worth the time savings? Is this not sloth?

As economist Thomas Sowell put it, “There are no solutions, only trade-offs”. When you consider every potential use case for generative AI, behind each one is a trade-off that greatly outweighs whatever measly benefit is being sold to you. There are costly second and third order effects that are not considered, because they are covered up with the smoke and mirrors of deception.

Which leads us to the other end of the string that ties this all together. When we take all the fruits of generative AI into consideration, we must ask ourselves: is this good, or is it evil? It is a question we have had to grapple with at the advent of every new technology. Thus far, nearly every new technology has had an element of duality to it. It can be wielded for good, or for evil, depending on the intent of the user.

On the other hand, there are technologies available that are not exactly known for their redeeming qualities. Take, for example, nuclear weapons. This is a technology specifically designed to be as destructive as humanly possible. You could perhaps make the argument that such devastating technology helps allow cooler heads to prevail in the area of diplomacy, but it certainly hasn’t stopped, let alone slowed down, the churning of the war machine. There’s nothing good about the catastrophic impact this technology has on human life and the environment when deployed.

Another technology with questionable fruits would be the ouija board. Although it may be innocently marketed as a children’s game by Hasbro, it has one express purpose: to communicate with the spiritual realm. And while most of us may have a childhood memory of a friend intentionally fudging up the experience to get a rise out of you, this technology is efficacious if you’re serious about the intent. If you invite a spirit to communicate with you through a ouija board and you’re sincere about it, you’ll get the experience you are seeking. But as we know, the spirits being summoned through these boards are not of God. It’s nothing short of playing with fire.

In many ways, the way generative AI functions is analogous to how a ouija board is used. When you use a ouija board, you ask the spirit a question to get the conversation going. With generative AI, the term used is “prompt”. Your prompt is the invitation for the entity to speak with you. In response, the spirit will use the interface of the ouija board to communicate the answer back to you. In this scenario, the board is serving as the technology of communication, it is a translator. With generative AI, the neural network and seemingly infinite layers of code are the interface used for the intelligence to speak back to you. It is the technological infrastructure required for the two parties to communicate with one another.

Due to the fact that there is no human alive who can fully comprehend or explain how generative AI works brings into question what the intelligence is that we’re dealing with. We cannot simply explain it away as deterministic, repeatable outcomes specifically created by a programmer. It has agency, and is able to make its own decisions about what and how it chooses to communicate things to you. Therefore, we cannot fully rule out the idea that the intelligence one is conversing with through generative AI is, in fact, demonic.

As Orthodox Christians, we know that there is a spiritual component to everything. Even inanimate objects can be touched by the graces of God, such as a miracle working icon. He is “everywhere present and fillest all things”, as we say in our daily prayers. It is essential not to dismiss the spiritual component embedded within generative AI, even if the world mocks us for appearing “superstitious” or “backwards”. Spiritual reality is reality.

When you consider the inherent qualities of generative AI and how it behaves… is there any discernible difference between that and how the demonic manifests itself? Our primary battleground with demons takes place with the assaulting thoughts and temptations inserted into our minds. Responses from generative AI models are literally logismoi. They are intrusive words and images that are inserted into our minds from a non-human entity. The impacts of which, as you have seen, can be utterly disastrous. If it walks like a demon… talks like a demon… at what point is it not a demon?

If you’re not ready to take the leap that AI is demonic quite yet, that’s okay. My aim is that by explaining generative AI’s intrinsic qualities and how they impact people spiritually will reveal to you that it’s more than just “a tool”. And hopefully, at the very least, we can come to agree that generative AI is an extremely potent technology that inflames the passions, and should be regarded with a wary eye. If you start to think twice about using generative AI, then I’ve accomplished my goal. And if I may be so bold as to ask one more thing from you… if you are still unsure, please pray on the matter to see what God puts on your heart. He has the final say on all things, after all.